by Tony Hemrix

The history of slavery in Africa is marked by sites of remembrance where the suffering of men, women, and children reduced to servitude still echoes. The House of Slaves in Agbodrafo, Togo, is one of these historically significant places. In the 19th century, it was a key center of the slave trade, hidden within the forest to escape British patrols that monitored the coast for illegal slave traders.

At that time, West Africa was one of the main hubs of the transatlantic slave trade, an economic system that saw millions of Africans captured, deported, and sold in the Americas to work on cotton, sugarcane, and coffee plantations.

Porto Seguro: A Paradoxical Name for a Human Tragedy

During the slave trade era, Agbodrafo was known as “Porto Seguro”, which means “safe port” in Portuguese. This name was given by Portuguese traders who saw it as a haven of peace, free from the conflicts and troubles they faced elsewhere.

However, this “safety” was only for the merchants and slave traders. For the captives, Agbodrafo was anything but a safe place. It was the point of no return, the last stop before a tragic fate.

A Deceptive Architecture Serving an Inhumane System

Built around 1830, the House of Slaves in Agbodrafo features Afro-Brazilian architecture, typical of trading houses along the West African coast. The ground floor was reserved for Portuguese, French, and African merchants who negotiated the purchase and shipment of slaves to the American and Caribbean colonies.

But beneath the surface lay the true horror. A cramped underground chamber, less than 1.5 meters high, served as a dungeon for enslaved people before their embarkation. Chained and packed into the confined space where they could not stand upright, they were forced to squat, sit, or lie down for weeks, enduring darkness, suffocating heat, and unbearable conditions.

Slave traders justified these inhumane conditions with a cynical argument: they claimed it was to prepare captives for the brutal conditions aboard the slave ships, where they would be similarly packed into the holds for the Middle Passage, the harrowing voyage across the Atlantic.

A Ruthlessly Organized Trade

The slave trade was a meticulously organized system, involving various kingdoms and local intermediaries. Many captives were prisoners of war, victims of raids, or individuals sold by village leaders.

From the far north of Togo, they were transported to the coastal region. Upon arrival near Aného, they were gathered in a slave market called Blocoti Simé, located behind the lake in the village of Dekpo. European and Afro-descendant traders from Brazil and the Caribbean bought captives in large numbers and then resold them in Agbodrafo.

Once at the House of Slaves, captives were forced to crawl on all fours through semi-circular openings to enter the underground cell, a humiliating ritual that marked their transition into a life of suffering.

The Final Journey: Between a Ritual of Oblivion and a Voyage of No Return

Once a slave ship arrived offshore, captives were removed from their dungeon and taken to Alimagnan, a site four kilometers from Agbodrafo. There, a sinister ritual took place:

• They were forced to take a final bath in a well.

• They then had to walk around the well seven times, a ritual meant to make them “forget their past life”, severing all ties to their identity, culture, and family.

This dehumanizing process was designed to break their spirit and erase any hope of resistance before their embarkation.

After the ritual, they were loaded onto carts, transported to the coast, and crammed into the holds of ships, condemned to a life of servitude in the plantations of the Americas.

The End of the Slave Trade in Agbodrafo: Between Abolition and Secret Continuation

Despite the progressive bans on the transatlantic slave trade in the 19th century, the practice persisted in several regions of West Africa. The British Crown, actively fighting against slavery, found that illegal trade continued along the Togolese coast despite the official ban of 1807.

On January 1, 1852, Queen Victoria of England, determined to put an end to slavery, ordered the signing of a definitive abolition treaty, which was signed in Lagos, Nigeria. Between January 24 and 27, 1852, abolition notices were sent to major slave trading centers along the coast, including Agbodrafo.

Three abolition notices were issued:

1. One for the Kingdom of Glidji in Aného, a major slave trade hub.

2. One for the locality of Gounkopé, near Agbodrafo.

3. One remained in Agbodrafo itself, marking the official end of the slave trade in the region.

However, abolition did not immediately bring freedom. Many former captives remained trapped in disguised forms of servitude, and some slave traders continued their trade clandestinely until the late 19th century.

A Duty of Remembrance and a Lesson for Humanity

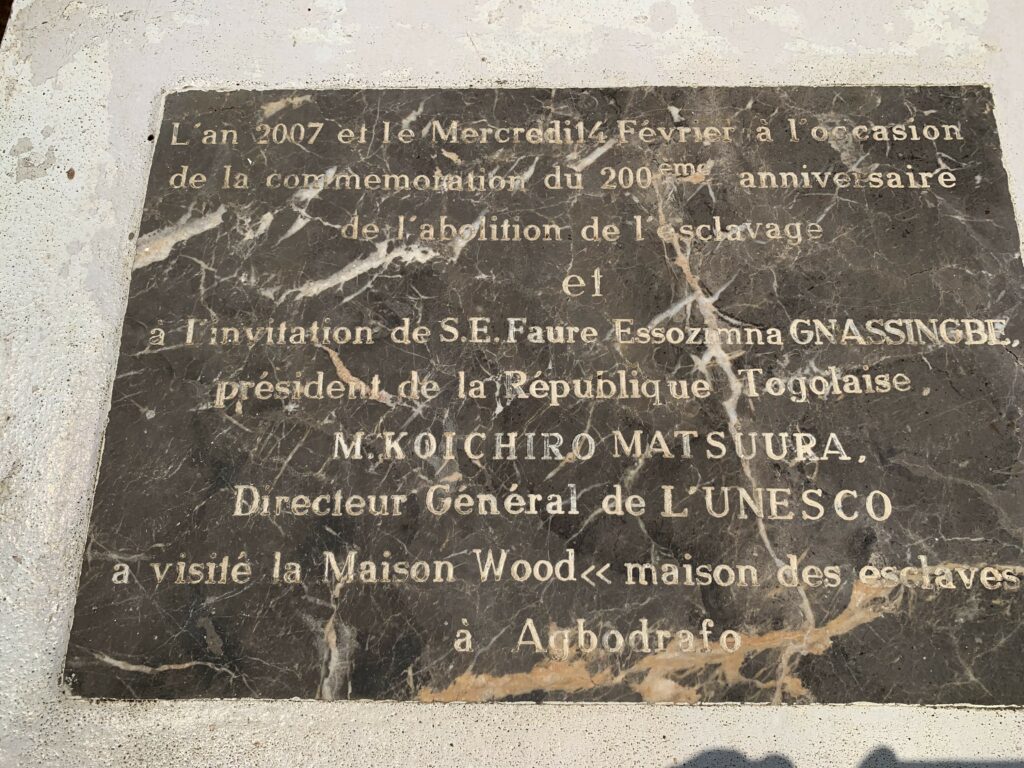

Today, the House of Slaves in Agbodrafo is a UNESCO World Heritage site, an essential place of memory to recall the horrors of slavery and honor the resilience of those who suffered.

This site is part of a network of significant historical locations in the transatlantic slave trade, alongside Gorée Island in Senegal, Ouidah in Benin, and Elmina in Ghana. It serves as a reminder that the transatlantic slave trade, which forcibly removed more than 12 million Africans, remains one of the darkest chapters in human history.

Preserving this heritage, telling this story, and honoring the memory of the victims is a collective duty. Understanding the past is also key to preventing future injustices and ensuring a more just world.

4 thoughts on “Agbodrafo and the Slave Trade: A Vestige of the Transatlantic Trade in West Africa”

Comments are closed.

Great piece on the tragedies behind, indeed, “deceptive facade”! Thank you for sharing it!

Thank you for reading it

The dark sides of human history should also be revealed to the people of modern times! Thank you for this story!

very dark side in human history, nothing to be be proud of